Melting of nanoparticles

Context

This project was partly motivated by the work at Nano Cluster Devices Limited – a Christchurch-based company making nanoscale devices by depositing metal nanoparticles on top of a grooved surface. Structural disintegration or misassembly due to melting was a concern to them, and it was more cost-effective to explore the issue using computer simulations before committing to more targeted (and relatively costly) experiments.

More motivation came from genuine curiosity and desire to learn how a fairly intuitive phenomenon, such as melting, can become ambiguous and counter-intuitive at the nanometre scale.

So, initially as a summer research student at Industrial Research Ltd (now Callaghan Innovation), I was tasked with running and analysing a series of simulations of model nanoparticles at gradually increasing temperatures, looking for anything out of the ordinary near the melting transition.

Methods

Simulations were carried out using several existing implementations of classical molecular dynamics (MD), which is a numerical method for stepping through Newton’s equations of motion for a given model system of interacting atoms.

To execute the simulations, I had to operate in a Linux environment and use command-line tools to launch jobs on a local computer cluster (through a queuing system).

I learned shell scripting and how to build data pipelines with grep, sed, and awk, which enabled me to rapidly process and analyse large volumes of structured data produced by my simulations.

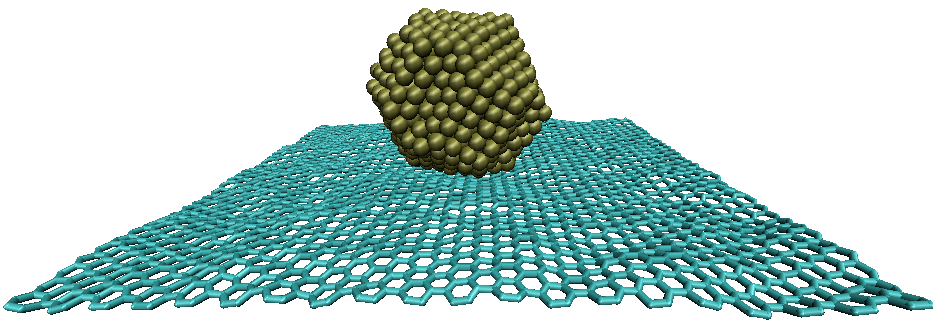

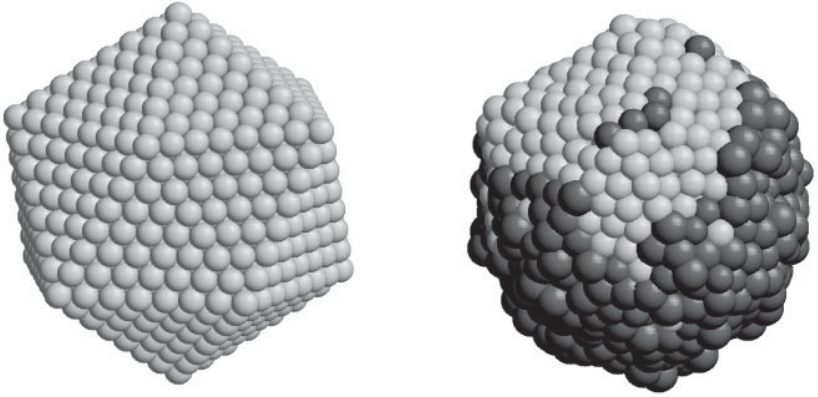

The analysis involved visual inspection and structural classification of 3D models, as shown in the figure above, as well as processing time-series data and using statistical techniques to calculate equilibrium averages.

Outputs

Some of the findings were indeed surprising! most notably that, in a partially molten cluster, the solid crystal-melt interface can cause

- sudden restructuring of the solid core; and

- super-heating, i.e. complete melting occurring at a temperature higher than the bulk melting temperature.

The latter observation was particularly counter-intuitive, because nanoparticles generally melt at lower temperatures compared to their bulk counterpart.

Finally, the findings opened up new lines of inquiry that led to my PhD in physics, which .